English follows Japanese (go to English version).

2024年のノーベル物理学賞および化学賞は機械学習手法の開発と応用に与えられました。アミノ酸配列からタンパク質の3次元構造を高精度で予測するAlphaFold2の出現により、化学分野での機械学習の有用性は決定的となりました。機械学習の信頼性が確立されたいま、本ブログの対象である有機合成分野のデータ科学の課題は、どのようなデータを創出するかにフォーカスされることになった、と言えるのかもしれません。その中で、筆者は有機合成・分子触媒分野における機械学習用データとして、DFT計算で算出した「触媒活性」および「遷移状態構造」に注目しています。今回は、機械学習 + 遷移状態計算による触媒設計について述べたいと思います。

有機合成分野では、DFT計算による触媒反応解析はいまや一般的になっています。学会に出て反応開発の講演を聞くと、かなりの確率でDFT・遷移状態計算による反応機構解析が含まれています。すでにDFT計算は反応という実現象を「観測」するのに欠かせない手段になっていると言っても過言ではありません。実験的に直接観測できない遷移状態を、DFT計算では観測できるという事実は触媒設計に多大なインパクトを与えるものと考えられます。しかし、遷移状態計算に基づく触媒設計は、もちろんその成功例はあるものの、有機合成化学者が日常的に使う手段とはまだなっていません。

遷移状態計算が触媒設計ツールとして浸透していない理由の一つとして、まっさきに思いつくのが誤差ではないでしょうか。たとえば、DFT計算による触媒設計研究の際によく引用される論文にはこのような記述があります(Nature 2008, 455, 309.)。

"The errors in absolute energies (typically ±5 kilocalories per mol) might therefore be larger than desired"

この記述をみると、DFTによる遷移状態計算の結果と実測値との誤差が触媒設計を困難にしている一因とも思えます。一方で、上記のように、DFT計算による反応機構解析は一般的となっていることから、その誤差は反応の観測には大きな影響を与えない、とも考えられます。誤差があるのに反応の観測ができるというのは一見矛盾しています。しかし、反応機構解析では絶対値を見るのではなく、活性・選択性が高い触媒と低い触媒を比較するなど、相対評価がほとんどです。さきほどの論文(Nature 2008, 455, 309.)でも、立体選択性などの相対比較では誤差が小さいといった記述もあります。

"but a much greater accuracy can be achieved when comparing several similar structures, for example the transition states of diastereomeric molecules."

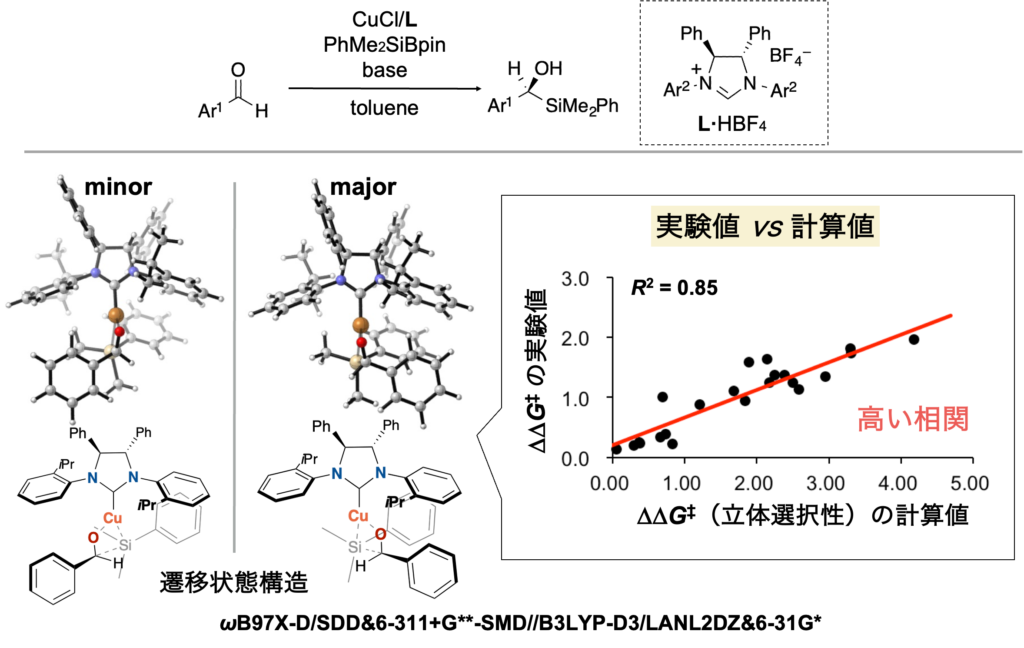

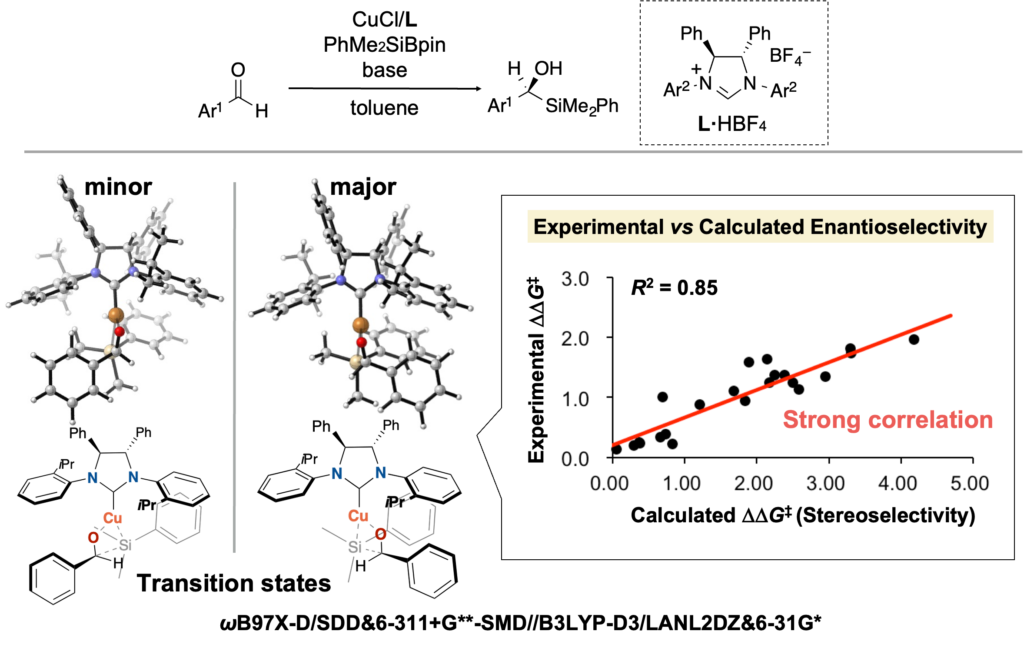

また実際に不斉触媒反応において、遷移状態計算で算出したエナンチオ選択性とその実験値とを比較すると、絶対値は大幅にずれているものの、高い相関を示します(下図、BCSJ 2022, 95, 271. 一部データ改変)。

この実験値と計算値の高い相関を見ると、実はDFT計算の誤差は必ずしも触媒設計を妨げる要因とはならないのではないかという考えが浮かびます。それでは触媒設計のためにDFT計算に必要なものはなんでしょうか?筆者は以下のように考えています。

触媒設計のためにDFT計算に必要なもの:解釈

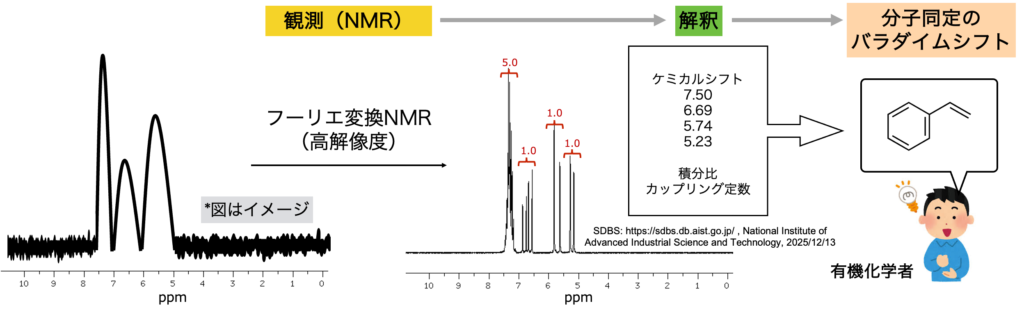

この「解釈」の重要性を、NMRを例に考えてみます。現在、有機分子の同定に欠かすことができないNMRですが、核磁気共鳴という現象自体は1940年代には固体や液体状態で「観測」されていました(https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1952/summary/)。しかし、NMRが有機合成の現場に普及する準備が整ったのは1960年代後半以降であり、核磁気共鳴の「観測」から、有機分子の同定におけるパラダイムシフトが実際に起こるまで20年以上の年月が必要でした。大きな要因の一つとして、核磁気共鳴が「観測」された当初、その「解釈」が難しかったことが挙げられます。NMRスペクトルから有機分子を同定するのに必要な情報の代表例として、ピークの位置と積分比およびカップリング定数があります。しかし1950年代では、NMRスペクトルの解像度は低く、有機合成の観点から現実的な時間スケールで上記情報を収集することは困難でした。

"~ in the late 1950s, NMR was an interesting tool, though its low sensitivity and the need for large samples made it far from being the method of choice to solve complicated chemical structures."

(以下より引用:https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/1991/speedread/)

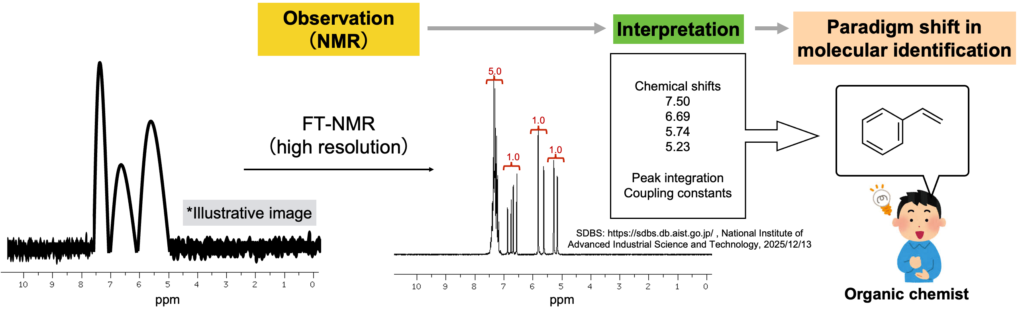

フーリエ変換NMRが登場し、シャープなピークが短時間で得られるようになることでスペクトルの「解釈」が可能となりました(下図)。有機分子同定のパラダイムシフトが起こり、今日の有機合成の発展につながっています。

それではDFT計算に話をもどします。遷移状態計算により、反応の「観測」はできているのではないか、ということを述べました。ではNMRで有機分子同定のパラダイムシフトを起こすのに必要な要素であった「解釈」はどうでしょうか?もちろん遷移状態構造の結合長を比較したり、原子の電荷を計算したりと、解釈のための手段は多々あるかと思います。しかし、遷移状態計算が触媒設計ツールとして一般化していないことから、設計につながるほどの高解像度の遷移状態に関する「解釈」を与える手段が、有機合成化学者が気軽に使える形では提供されていないと筆者は考えています。

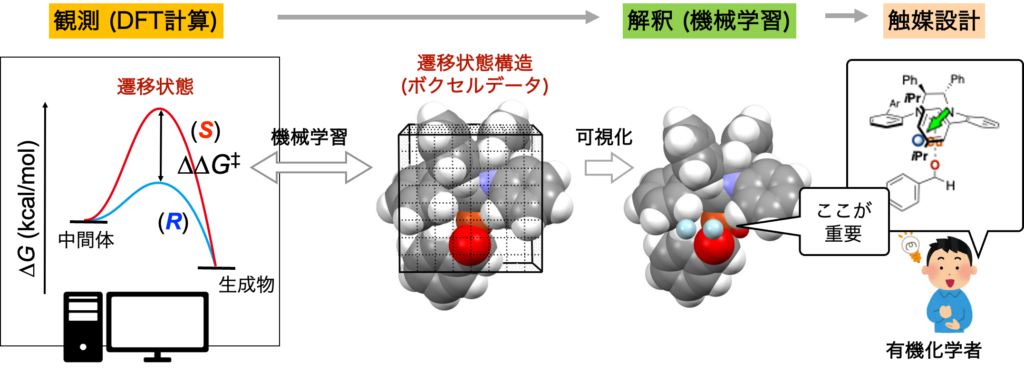

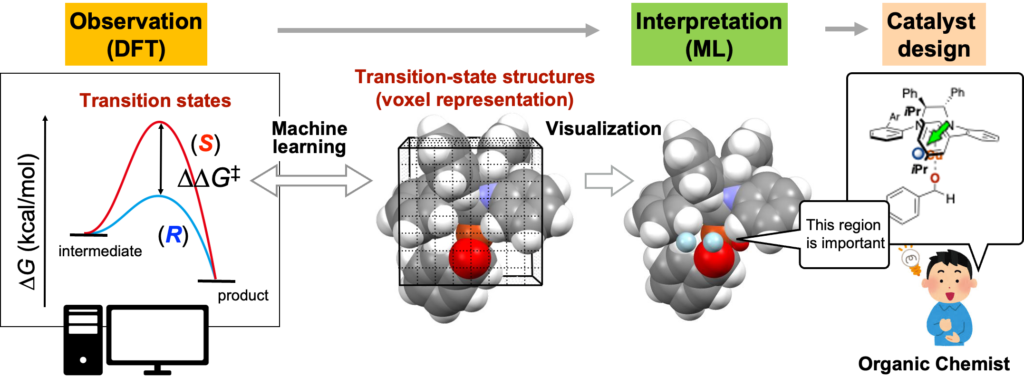

ここで最初に述べた機械学習 + 遷移状態計算による触媒設計が登場します。筆者は、遷移状態計算の結果を「解釈」するための手段として、機械学習に注目しています。上述のように不斉触媒反応を解析すると、相対的には立体選択性の計算値と実験値には高い相関があることが確認できます。DFT計算で算出した「触媒活性」および「遷移状態構造」のデータ解析を行うことで、触媒能(この場合、立体選択性)の支配因子に関する情報を抽出でき、触媒設計につながる遷移状態の「解釈」が可能になります。具体的には、下図のように遷移状態構造をボクセルデータ(2次元画像データであるピクセルデータの3次元版)に変換し、∆∆G‡の計算値(立体選択性の計算値)との間で回帰分析をすることで、遷移状態構造のどの部分が立体選択性に重要なのかを可視化できます(下図の水色部分が重要)。可視化した情報をもとに人間がメカニズムの解釈を行い、また可視化した領域に重なるように置換基を導入することで、立体選択性が向上する触媒が設計できます(BCSJ 2022, 95, 271. 理研プレスリリース)。

ここで不斉触媒反応では、生成物の立体選択性の比は、上図のような各エナンチオマーに通じる遷移状態のエネルギー差(∆∆G‡)に対応します。比較的容易に実験で物理的に意味のある質のよいデータが収集できるため、以前にも述べたように近年、不斉触媒反応のデータ解析が盛んに研究されています。

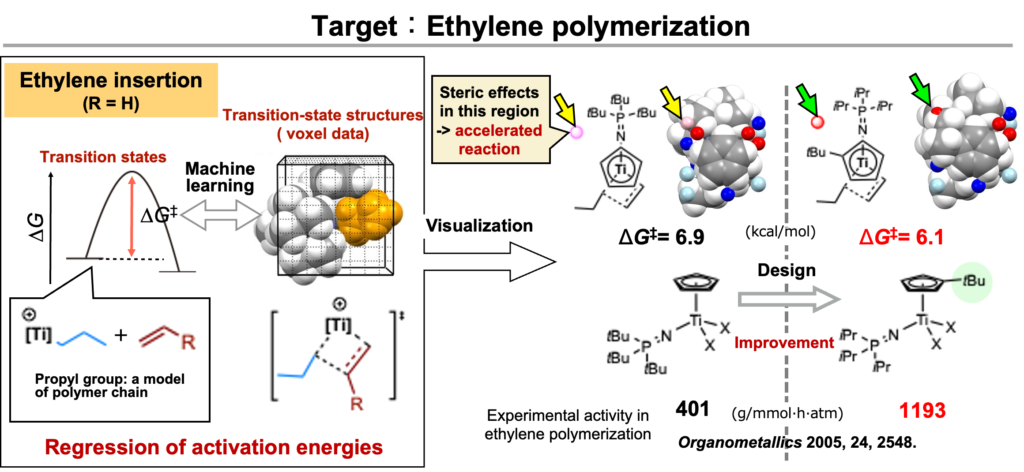

一方で遷移状態計算では、実験では難しい活性化エネルギーのデータ収集が可能です。ハーフチタノセン触媒によるエチレン重合を対象に、エチレン挿入の活性化エネルギーと、遷移状態構造のボクセルデータを用いた回帰分析を行うことで、活性が向上する触媒設計のデモンストレーションも報告しています(下図、Catal. Sci. Technol. 2024, 14, 2434.:ここでは高分子の分子量制御のデモンストレーションも同時に行っています。複数のreaction outcomeの制御は大変面白くかつ重要な研究対象ですが、そのお話はまた後日どこかでまとめたいと思います)。

ここで興味深いのは、置換基を導入すると活性化エネルギーが下がる(=触媒活性が向上する)領域が回帰分析により抽出できたことです(上図の赤点)。その領域に置換基を導入することで、歪みエネルギーが小さくなることを確認しています。置換基の立体効果が、錯体の構造をエチレン挿入の遷移状態に近づけているとも解釈できる結果が得られました。この解釈をもとに上図の分子設計をしています。Pd触媒によるクロスカップリングでは立体障害により還元的脱離が加速されるのはよく知られていますが、立体障害で重合におけるオレフィン挿入が加速されるという仮説は、データ解析なしで、筆者の直感のみでは思い至るのは困難でした。

このように遷移状態計算+機械学習という枠組みは、遷移状態の解釈を与え、触媒設計につながる手段となり得ます。もちろんカウンターアニオンの効果がある系など、反応性を記述する要素を遷移状態計算に十分に取り込みにくい場合は実験の再現が難しいこともあります。しかし、そういった系でも触媒主骨格はデータ科学に基づき設計し、カウンターアニオンは研究者の直感で制御するなど、すべてを研究者の直感で制御する場合に比べ、考えるべき要素を格段に減らすことができます(上記データ駆動型オレフィン重合触媒設計がまさにその例となっています。ご興味ある方は論文をご覧ください。)。

以上、今回は、有機合成分野のデータ科学の課題であるどのようなデータを創出するかという観点から、機械学習 + 遷移状態計算による触媒設計についてふれました。遷移状態計算では反応の「観測」はできているが、触媒設計につなげるにはその「解釈」のための方法論を有機合成化学者が扱いやすい形で提供する必要があるという筆者の考えについて述べました。この考えのもと、遷移状態計算と機械学習を組み合わせることで、触媒設計が可能なレベルの高解像度で、遷移状態に関する「解釈」ができることを紹介しました。さらに上述のように、遷移状態計算の長所として、通常ではデータ収集が難しい活性化エネルギーの制御もできます。同様の枠組みで触媒設計を試したいアカデミアの方向けに、webアプリ(https://mcds.riken.jp)を公開しています(下記はそのデモ動画)。

機械学習 + 遷移状態計算による触媒設計という枠組みには、今回紹介した特徴に加えて、有機合成分野のデータ科学の常識を覆すポテンシャルがあります。具体的には、この枠組みを用いると異種反応間の統合解析に基づく触媒設計が可能となります。次回はこの「統合触媒科学」という枠組みについてご紹介します。

(以下、英語版)

What is required for catalyst design based on DFT calculations

The 2024 Nobel Prizes in Physics and Chemistry were awarded for the development and application of machine learning methods. With the advent of AlphaFold2, which enables highly accurate prediction of three-dimensional protein structures from amino acid sequences, the usefulness of machine learning in chemistry has become firmly established.

Now that the reliability of machine learning methods is widely recognized, the key challenge for data science in organic synthesis (the main focus of this blog) may no longer lie in how to apply machine learning, but rather in what kind of data should be generated.

In this context, I focus on “catalytic activity” and “transition-state structures” obtained from DFT calculations as data suitable for machine-learning applications in organic synthesis and molecular catalysis. In this article, I discuss catalyst design based on the combination of machine learning and transition-state calculations.

In the field of organic synthesis, the analysis of catalytic reactions using DFT calculations has become routine. If you attend conferences related to organic chemistry, you can find that presentations on reaction development very often include mechanistic studies based on transition-state calculations. It means that DFT calculations have become an indispensable tool for “observing” chemical reactions.

The fact that transition states, which cannot be directly observed experimentally, can be examined through DFT calculations should have a profound impact on catalyst design. Nevertheless, despite several notable successes, catalyst design based on transition-state calculations has not yet become a method that organic chemists routinely use in their day-to-day research.

One possible reason why transition-state calculations have not yet become widely adopted as a practical tool for catalyst design is the presence of errors, which is perhaps the first issue that comes to mind. For example, a frequently cited paper in studies on computational catalyst design includes the following statement (Nature 2008, 455, 309):

"The errors in absolute energies (typically ±5 kilocalories per mol) might therefore be larger than desired"

At first glance, this statement suggests that the discrepancy between DFT-based transition-state energies and experimental values may be one factor that makes computational catalyst design difficult. On the other hand, as discussed above, mechanistic studies of reactions based on DFT calculations have become commonplace, implying that such errors do not necessarily prevent the “observation” of chemical reactions.

It may seem contradictory that reactions can be observed despite the presence of significant errors. However, in mechanistic studies, absolute values are rarely the focus; instead, catalysts with high activity or selectivity are typically compared with those showing lower performance. In other words, relative evaluation is the norm. Indeed, the same paper (Nature 2008, 455, 309) also notes that errors are much smaller in relative comparisons, such as those involving stereoselectivity:

"but a much greater accuracy can be achieved when comparing several similar structures, for example the transition states of diastereomeric molecules."

Consistent with this view, in an example of an asymmetric catalytic reaction, a comparison between DFT-calculated and experimental enantioselectivities shows substantial deviations in absolute values, yet exhibits a high degree of correlation as shown below (BCSJ 2022, 95, 271; data partially modified).

The high correlation between experimental and calculated values discussed above suggests that errors in DFT calculations may not necessarily be a fundamental obstacle to catalyst design. This raises the question: what, then, is required for effective catalyst design based on DFT calculations? I propose the following answer.

What is required for catalyst design based on DFT calculations: interpretation

To illustrate the importance of “interpretation,” it is instructive to consider the example of NMR spectroscopy. Although NMR is now indispensable for the identification of organic molecules, the phenomenon of nuclear magnetic resonance itself had already been observed in solids and liquids as early as the 1940s (https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1952/summary/). However, it was not until the late 1960s that NMR became sufficiently established for widespread use in organic synthesis, leading to a paradigm shift in molecular identification more than two decades after the initial observation.

One major reason for this delay was that its interpretation remained difficult in the early period following the initial observation of nuclear magnetic resonance. Key information required to identify organic molecules from NMR spectra include chemical shifts, peak integration, and coupling constants. In the 1950s, however, the spectral resolution of NMR was limited, making it difficult to acquire such information on a practical time scale from the perspective of organic synthesis.

"~ in the late 1950s, NMR was an interesting tool, though its low sensitivity and the need for large samples made it far from being the method of choice to solve complicated chemical structures."

(quote from:https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/1991/speedread/)

With the advent of Fourier-transform NMR, sharp spectra could be obtained within a short time, enabling reliable interpretation of NMR data (see figure below). This development triggered a paradigm shift in the identification of organic molecules and contributed to the remarkable progress of modern organic synthesis.

Let us now return to DFT calculations. As discussed above, transition-state calculations allow us to observe chemical reactions in a meaningful sense. The key question, then, is how transition-state calculations can be interpreted in a way that enables catalyst design, analogous to the role of interpretation in the paradigm shift in NMR-based molecular identification. Of course, various approaches for interpreting transition states already exist, such as comparing bond lengths or analyzing atomic charges.

Nevertheless, the fact that transition-state calculations have not yet become a standard tool for catalyst design suggests that methods capable of providing sufficiently high-resolution interpretation of transition states at a level directly relevant to design are still lacking in a form that organic chemists can readily use.

It is in this context that catalyst design based on the combination of machine learning and transition-state calculations becomes relevant. I focus on machine learning as a powerful means of interpreting the results of transition-state calculations. As mentioned above, analyses of asymmetric catalytic reactions indicate that, when considered comparatively, calculated and experimental stereoselectivities can exhibit a high degree of correlation. Through data analysis of “catalytic activity” and “transition-state structures” obtained from DFT calculations, it becomes possible to extract information on the factors governing catalytic activity (in this case, stereoselectivity) and thereby achieve an interpretation of transition states that directly informs catalyst design.

More specifically, as illustrated in the figure below, transition-state structures can be converted into voxel data (the three-dimensional analogue of two-dimensional pixel data) and subjected to regression analysis against calculated ∆∆G‡ values, which correspond to stereoselectivity. This approach enables visualization of which regions of the transition-state structure are important for stereoselectivity (indicated by light blue points in the figure). Based on this visualized information, human insight can be applied to interpret the reaction mechanism, and substituents can be introduced so as to overlap with the identified regions, leading to the rational design of catalysts with improved stereoselectivity (BCSJ 2022, 95, 271.).

In asymmetric catalytic reactions, the ratio of product stereoisomers corresponds to the energy difference between the transition states leading to each enantiomer (∆∆G‡), as illustrated in the figure above. This relationship means that experimental stereoselectivity values constitute high-quality data with clear physical meaning. As a result, data analysis of asymmetric catalytic reactions has been actively pursued in recent years.

In contrast, transition-state calculations allow access to activation energies that are often difficult to obtain experimentally. In half-titanocene-catalyzed ethylene polymerization, we have shown that regression analysis linking activation energies for ethylene insertion with digitized transition-state structures (voxel data) enables the design of a catalyst with enhanced activity (see figure below; Catal. Sci. Technol. 2024, 95, 271.). In that study, control of polymer molecular weight was also demonstrated. The simultaneous control of multiple reaction outcomes is an especially intriguing and important research direction, which will be discussed elsewhere in the future.

A particularly interesting outcome of this analysis is that regression identifies regions where the introduction of substituents lowers the activation energy, corresponding to enhanced catalytic activity (red points in the figure above). Introducing substituents in these regions was found to reduce the distortion energy of the transition state. This result can be interpreted as a steric effect that shifts the catalyst structure closer to the transition state for ethylene insertion, and the molecular design shown above was guided by this interpretation.

In Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions, it is well known that steric bulk can accelerate reductive elimination. By contrast, the idea that steric effects could also accelerate olefin insertion in polymerization reactions would have been difficult to arrive at based on my intuition alone, without guidance from data analysis.

In this way, the combination of transition-state calculations and machine learning provides a framework for interpreting transition states and can serve as an effective route toward catalyst design. Of course, there are cases in which experimental behavior is difficult to reproduce, such as systems where reactivity is strongly influenced by factors that are not easily incorporated into transition-state calculations, including counterion effects.

Even in such cases, however, the catalyst core structure can be designed based on a data-driven workflow, while other elements, such as interactions with counterions, can be tuned using chemical intuition. Compared with relying entirely on intuition, this approach substantially reduces the number of factors that must be considered. The data-driven design of olefin polymerization catalysts discussed above provides a representative example of this strategy.

In summary, this article has discussed catalyst design based on the combination of machine learning and transition-state calculations, from the perspective of what types of data should be generated for data science in organic synthesis. I have argued that, although transition-state calculations already allow the “observation” of reactions, their effective use in catalyst design requires methods for “interpretation” that are accessible to practicing organic chemists.

Within this framework, I have shown that combining transition-state calculations with machine learning enables high-resolution interpretation of transition states at a level sufficient for catalyst design. In addition, as discussed above, an important advantage of transition-state calculations is that they provide access to activation energies, which are difficult to obtain experimentally. For academic researchers interested in exploring catalyst design within this framework, a free web application (https://mcds.riken.jp) is available (a demonstration video).

Beyond the features discussed here, the framework of catalyst design based on the combination of machine learning and transition-state calculations has the potential to fundamentally reshape data science in organic synthesis. In particular, this approach enables catalyst design based on the integrated analysis of data across different types of reactions. In the next article, I will introduce this emerging concept, which I refer to as “Integrated Catalysis Science”.